5 What Is Knowing?

TL;DR: close GitHub issues, commit a “final” draft, deploy your web portfolio

readings (links) & lectures ~ assignments due ~ live session agenda

Figure 14: “Kant via the categorical imperative is holding that ontologically it exists only in the imagination.”

This week we transition to the middle of the course where we will deal explicitly with research design from a more academic perspective. Soon you will you proud to explain the difference between epistemology and ontology to your friends and family. The readings are a trip this week; we think you’ll enjoy them.

Your assignment is to put the finishing touches on Portfolio Design 1, utilizing all of the insights your friends have generously provided you.

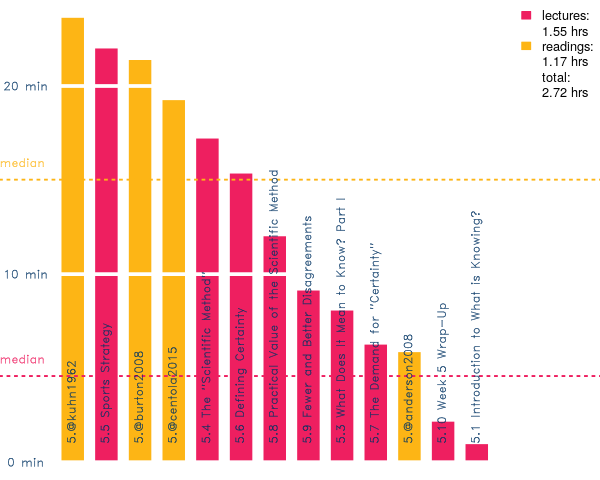

Figure 15: Week 5 “reading” time estimated at 250 words per minute

Readings

Lectures

- ↓ 5.1 Introduction to What is Knowing?

- ↓ 5.3 What Does It Mean to Know? Part I

- ↓ 5.3.1 What Does It Mean to Know? Part II

- ↓ 5.4 The “Scientific Method”

- ↓ 5.4.1 The Real Scientific Method

- ↓ 5.4.2 Tests and Data in Health Care: Michael Wollin

- ↓ 5.5 Sports Strategy

- ↓ 5.5.1 Deception in Sports

- ↓ 5.5.2.1 Your Own Data Deception

- ↓ 5.6 Defining Certainty

- ↓ 5.6.1 How Experts View Certainty: Craig Denny

- ↓ 5.6.2 ACH Instructions

- ↓ 5.7 The Demand for “Certainty”

- ↓ 5.8 Practical Value of the Scientific Method

- ↓ 5.8.1 Scientific Method Examples

- ↓ 5.8.2 Popper and Kuhn

- ↓ 5.9 Fewer and Better Disagreements

- ↓ 5.9.1 Fewer and Better Disagreements Examples: Baruch Fischoff

- ↓ 5.10 Week 5 Wrap-Up

5.1 Introduction to What is Knowing? ↑

| Players | Slug | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| γ σ | shared notion | how it is that people who come from different paradigms who are actually starting with very different assumptions about what’s happening in their business, what’s happening in the world, what’s happening in their personal lives, can have more constructive conversations by referring to some sort of shared notion of what it means to know something |

5.3 What Does It Mean to Know? Part I ↑

| Players | Slug | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| α ζ | know to act | What does it actually mean to know something so that you can act on it? |

| χ κ | epistemology | the word “epistemology,” which is probably too complicated for what it sounds like. But it’s really just in a very practical sense a kind of theory of knowledge or a notion of, what does it mean to have knowledge, and how broadly can one apply it? |

| π φ | agree to agree | how we as a community of actors, or maybe as a company or maybe a group of people in a room, how we are going to decide amongst ourselves and agree with each other that something is true. |

| τ χ | practical art | Epistemology is a philosophy that people have been struggling with for thousands of years. For us, it’s really a practical art. |

| π σ | teacher questions | As a college teacher, I really would like to find a way to know if I’m helping my students learn what they need to know 20 or 30 years later. In other words, are they becoming better citizens? Are they better workers? Are they happier? Are they more satisfied in their lives because of something I taught them? |

| λ ε | too late | even if I could collect the data for a scientific assessment of that, that data is not going to be available for 15, 20, maybe 30 years, and by that time, it’s too late for me to go back and change how I taught them 30 years earlier. That’s just not useful for my purposes. |

| ξ η | standards of truth | There can be very different standards of truth depending on what kind of decision you want to make. |

| ζ χ | Tesla | you’re, say, working for Tesla and you’re trying to decide, what do you think the most popular paint color is going to be for the car next year? And we’re going to have to plan our build runs in the factory. That’s a piece of data, a piece of knowledge. And we could argue about whether we’ve got it right, but the cost of not getting it right are things we might be able to manage. |

| ο λ | White House | say, you’re sitting in the White House in the United States and you’re trying to decide, is this rebel group in a country in the middle of a civil war taking money or not from a terrorist organization? That might be a different standard of truth. |

| ι ο | hospital | if you’re sitting in a hospital and you’re thinking about, again, an experimental medical treatment, you might want another standard of truth to apply to, say, stage three clinical trials for an anti-cancer drug or an anti-dementia treatment. You wouldn’t want to have to apply the same standard of truth to all of those three cases, because the stakes are really different. |

| λ κ | proof not truth | the most important arguments in the real world are actually not over whether something is said is true. That’s not what people really argue about, although they do. What really matters in most decision-making situations happens prior to that discussion. It’s actually the argument over what standard of proof ought to be applied. |

| ο ι | data science advisors | if we think of ourselves as data science advisors, then helping the people around us to do that in a way that makes what we have to bring to the table– the data– most effective and most beneficial inside the organization. |

5.3.1 What Does It Mean to Know? Part II ↑

| Players | Slug | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| τ γ | #1 correspondence | true beliefs and true statements, things that are true, correspond to the actual state of affairs in the world– what’s really happening. |

| υ δ | simplify exaggerate complexify | the whole point of a model in any of those domains is to simplify, exaggerate the important stuff, and then add the complexity back. A model that was an accurate representation of reality wouldn’t be a model anymore |

| ν α | non-correspondence of symbols | for purists, the model would still need to be described in words or symbols. And since neither of those perfectly represent reality, there’s always going to be some form of non-correspondence. |

| η ψ | #2 social construction | What counts as truth is really a social construction– what people in a specific place at a specific time agree amongst themselves is true. And in this view, what is true depends on culture, depends on history, and of course, it depends on who’s powerful. |

| β δ | extraordinary success | If you’re respected for having been extraordinarily successful these days in a technology startup, you get the power to define what is or ought to be true in other areas of human action. |

| ι κ | Bill Gates | He was extraordinarily successful in technology and he’s now getting to define what is true in these other areas. |

| σ κ | truth and identity | the CEO actually gets to define what is true inside that company. Think about someone saying, you know, we are a design company. That’s not just a statement about what’s true, that’s a statement about who we are. |

| γ ζ | brute fact | Knock on a wooden desk. [KNOCK] You know, that’s a brute fact. What you just hit your head on is wood. |

| μ ι | social fact | But it’s a social fact that it’s a desk. Nothing in nature says, we sit at this desk and work. In some other society, people might think this is a prayer bench. Somewhere else, people might agree that it’s god. |

| ξ α | #3 clash of arguments | John Stuart Mill, you probably know, was a British philosopher and economist from the mid 1800s. He argued that truth is something that human beings arrive at. And the way they arrive at it is through a particular form of argumentation– the clash of opposing viewpoints. |

| ι γ | hard-edged debate | Think of truth is what you get closer to over time kind of asymptomatically through hard-edged debate. You know, you take this position. I take that position. We bang them up against each other. We do that over and over again. And over time, the debate kind of starts to extrude the false statements and selects for the one that are closer to the truth. |

| ψ δ | corrosion | truth has a kind of entropy built into it, that it tends to corrode over time, and that if you don’t constantly reinforce it, it will corrode. |

| υ α | can’t win only once | You can’t win the truth debate only once. But it’s a hard notion for people who are scientifically and technically minded to accept. I mean, once we know something is true, unless the environment changes, why should that truth corrode. But think about how you’ve lived that reality in your own business. |

| χ δ | important actionable truths | How can you most effectively move the search for important, actionable truths forward inside a real, living, breathing company? |

5.4 The “Scientific Method” ↑

| Players | Slug | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| η κ | b&w step 1 | In general, we look for a new law by the following process. First we guess it. [AUDIENCE LAUGHS] |

| ο θ | b&w step 2 | Then we compute the consequences of the guess to see what– if this is right. If this law that we guessed is right, we see what it would imply. |

| α φ | b&w step 3 | then we compare those computation results to nature. Or we say compare to experiment or experience. Compare it directly with observations to see if it works. |

| β λ | b&w step 4 | If it disagrees with experiment, it’s wrong. In that simple statement is the key to science. |

| μ δ | All there is to it | It doesn’t make a difference how beautiful your guess is, it doesn’t make a difference how smart you are who made the guess, or what his name is, if it disagreed with experiment, it’s wrong. That’s all there is to it. |

5.4.1 The Real Scientific Method ↑

| Players | Slug | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| χ τ | #1 formulate the question | And for most people, this is actually the most important part. And when you dig into it, there’s a lot of disagreement on what are actually the best kinds of questions |

| χ π | really nasty things | poorly formulated questions are just really nasty things. They waste enormous amounts of time– effort. They cause confusion. They cause frustration. Everybody hates them. |

| β θ | simple advice | we’ve all seen questions that we just know from the beginning can’t be answered through scientific reasoning of the kind that we’re going to do with data. So I have really simple advice about that. Don’t ask those kinds of questions. And don’t let people around you ask them. |

| ξ ε | #2 establish priors | find out what’s already known that bears on this question. |

| ε α | lost and found | there might be a piece of knowledge out there tested and confirmed perhaps that you really or I really would have wanted to know before I started my experiments or my research, but I just wouldn’t know about it because I wouldn’t have found it. |

| ξ κ | no problem | we like to imagine that today, searching for the existing literature or finding out what’s already known about a question has become really easy. |

| φ ρ | competitive aspect | There are people out there who don’t want you to know what’s already known about this question, whatever it is. My grandmother in Brooklyn used to say, does Macy’s tell Gimbels? |

| ψ ω | analysis paralysis | when and where do you stop searching for relevant preexisting knowledge and proceed with your own experiment. The web has made it really easy to just keep searching. |

| σ η | #3 generate a hypothesis | Think of it as a hunch. |

| ξ φ | have a reason | The best hypotheses are those that you draw for a reason. You have a reason to expect the answer to be x rather than y, maybe because of some other knowledge that you have, maybe because you have confidence in a theory which suggests that, even though it hasn’t been proven. |

| γ ρ | or not | sometimes hypotheses are actually just more like random guesses or gut feelings. |

| ι ζ | #4 willingness to discard | the basis for a hypothesis in practice has a big impact on how quickly or how slowly we’re going to be willing to discard it if a bad or discrepant piece of data comes in that suggests it’s wrong. |

| ω α | reject hypothesis or experiment | We might be a little bit more resistant to discarding the hypothesis if we have deep reason to expect that it’s right– could be that the experiment was faulty in some way. |

| η β | #5 experiment | everybody wants to jump to that as soon as possible. |

| υ ζ | it’s hard | I want to get that hypothesis, I want to make predictions about something that could happen, and I want to design an experiment that evaluates whether those predictions are correct. And I want to get to it as quickly as I possibly can, but it’s hard. |

| ι δ | prior acceptance | Progress towards shared understandings in real-world decision situations just depends enormously on prior acceptance by the people you’re trying to convince that the experiment that you are proposing is a reasonable one to test the hypothesis. |

| ο ψ | easy criticism | Otherwise, it’s just going to be too easy for people who don’t like your findings to come back later and criticize the design of the experiment. |

| π τ | intellectual and emotional opposition | It is very rare that the findings are going to be so compelling that they’re simply going to overcome the intellectual and emotional opposition of people who don’t want to believe what you have to tell them. |

| φ σ | #678∞ | you need to analyze the results of the experiment, draw the appropriate and justified conclusions, communicate the results, and then, of course, iterate. It never ends. What matters here? The obvious stuff– precise analysis, the right level of confidence in the conclusions, and crystal clear communication about both of those things to everybody around you. |

| ν γ | hard cases | I said before, it’s 2003. Does Iraq have weapons of mass destruction? Or to point to the example we’re about to look at, it’s 1999. Wen Ho Lee, a Chinese scientist at Los Alamos National Labs, is accused of spying. Is he guilty? |

| φ χ | analysis of competing hypotheses | 30 years in development for high stakes, hard issues, ambiguous questions, where it’s not just one person trying to figure out what’s right but lots and lots of people, many analysts, all of whom are touching a piece of the story and seeing different pieces of evidence in different ways. |

5.4.2 Tests and Data in Health Care: Michael Wollin ↑

| Players | Slug | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| ι ω | 1908s | in the ’80s, in fact, when I started my residency, prostate cancer was very prevalent. But when men were diagnosed with prostate cancer, 75% of men already had advanced disease, because there was no test to determine whether one had prostate cancer unless the man was symptomatic. |

| ο λ | 1990s | in 1994, found that in conjunction with a digital rectal exam, in asymptomatic men, maybe this PSA, prostate specific antigen, could be a marker to detect preclinical evidence of prostate cancer. And it was approved by the FDA as a screening test for prostate cancer. |

| ι ε | wonderful? | we now have a blood test that’s going to pick up prostate cancer. Isn’t that wonderful? |

| κ γ | false positives | the PSA not only is elevated in men with prostate cancer, but, as in all tests with false positives, it can be elevated in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia, or enlargement of the prostate, infections, urinary tract infections, or prostatitis |

| η ζ | incidentalomas | when you first get a new screening test you pick up lots of abnormal formations or things that look abnormal because you don’t really have a really definitive baseline for what is normal. |

| ι ν | anybody over 4 | Anybody over 4 early on was biopsied. When they found out that too many men were being biopsied, they tried to look at age-specific PSA levels, such that younger men with lower PSAs at detecting cancer, and older men may have high PSAs that just go along with older age. |

| ξ ι | false negatives | You can have a normal PSA and still have prostate cancer. |

| μ ο | 90 year old | if a man lives long enough, i.e. 90 years of age, there’s a 90% to 100% chance that, at an autopsy, he will have prostate cancer cells in his prostate. |

| τ α | 20 year old | they took young men in their 20s who were dying in war, and they autopsied their prostate, and they found that 10% of those men already had prostate cancer cells. |

| ξ μ | natural aging phenomenon | The problem becomes does having detection of these cells correlate with clinical cancer. So you have to look at a prevalence of a condition, which is very prevalent versus the clinical incidence of a disease. |

| τ ρ | only one case | the only case that matters is the one in front of you, or behind you, or inside of you as the case may be. |

| κ ε | the word cancer | we don’t treat society, we treat an individual, and there’s some emotional overlay in terms of when you use the word cancer. Now, you hear the word cancer, and right away it strikes fear. |

| ε γ | selection bias | Since you have a very, very slow doubling time, and you have a very long period of time to pick up with the detection, slow-growing disease, you tend to pick up the slower-growing diseases more prevalently than the aggressive ones. |

| ψ ο | treatment morbidity | because we have the ability, with a screening test, to pick up things early. And we treat if we’re not going to change the natural history of the disease. We’re probably going to hurt more people with our treatment than we would if we didn’t even detect the cancers in the first place. |

| δ σ | survival | recently the US Preventive Services Task Force analyzed data, and they analyzed data from several studies, including the Prostate, Lung, Colon, Ovarian Screening Trial that the NCI conducted. And that was a study that found that if men screened– obviously if you screen men you increase the detection of prostate cancer, but if you treat those men, survival was not influenced. |

| η δ | 1 and 999 lives | the US Preventive Task Force, said that you have to screen 1,000 men to possibly save one life. So you have to put 999 men through screening, and screening carries risks. |

| β ε | PSA cripples | we’ve created this population of men who are so focused on their PSAs, asymptomatic men in fact. Or you treat these men, and then they have morbidities |

| μ ο | PSA velocity | in our practice, as we’ve seen lately, there’s been less and less referrals for men with elevated PSAs. We do look at PSA velocity which is really the change of PSA over time. |

| μ γ | stop screening? | A lot of primary care doctors are not screening for prostate cancer at all. |

| δ τ | who to worry about | The men we do worry about, there seems to be data that in African-Americans or in men with a first degree relative, a father or a brother who had prostate cancer, the incidence is greater. |

| θ ι | do and don’t | I can cure the prostate cancers I don’t need to, but I still can’t cure the cancers I do need to. |

| τ π | exciting to worthless | PSA was initially highlighted in ’94– very exciting. Everybody jumped on it and it’s gotten grayer and grayer over a 20-year period of time, almost to the point now where people are saying it’s a worthless test. |

5.5 Sports Strategy ↑

| Players | Slug | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| ε ι | NA | NA |

5.5.1 Deception in Sports ↑

| Players | Slug | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| κ θ | NA | NA |

5.5.2.1 Your Own Data Deception ↑

| Players | Slug | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| κ α | NA | NA |

5.5.2.2 ↑

| Players | Slug | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| υ τ | NA | NA |

5.5.2.3 ↑

| Players | Slug | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| δ ι | NA | NA |

5.5.2.4 ↑

| Players | Slug | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| ν σ | NA | NA |

5.5.2.5 ↑

| Players | Slug | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| λ θ | NA | NA |

5.5.2.6 ↑

| Players | Slug | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| μ ν | NA | NA |

5.5.2.7 ↑

| Players | Slug | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| ε γ | NA | NA |

5.5.2.8 ↑

| Players | Slug | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| γ ξ | NA | NA |

5.5.2.9 ↑

| Players | Slug | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| θ φ | NA | NA |

5.6 Defining Certainty ↑

| Players | Slug | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| φ α | NA | NA |

5.6.1 How Experts View Certainty: Craig Denny ↑

| Players | Slug | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| ρ ζ | NA | NA |

5.6.2 ACH Instructions ↑

| Players | Slug | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| β ω | NA | NA |

5.7 The Demand for “Certainty” ↑

| Players | Slug | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| μ φ | NA | NA |

5.8 Practical Value of the Scientific Method ↑

| Players | Slug | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| π ψ | NA | NA |

5.8.1 Scientific Method Examples ↑

| Players | Slug | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| χ μ | NA | NA |

5.8.2 Popper and Kuhn ↑

| Players | Slug | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| χ κ | NA | NA |

5.9 Fewer and Better Disagreements ↑

| Players | Slug | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| ω ψ | NA | NA |

5.9.1 Fewer and Better Disagreements Examples: Baruch Fischoff ↑

| Players | Slug | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| π γ | NA | NA |

Bibliography

Anderson, Chris. 2008. “The End of Theory: The Data Deluge Makes the Scientific Method Obsolete WIRED,” June. https://www.wired.com/2008/06/pb-theory/.

Burton, Robert Alan. 2008. On Being Certain : Believing You Are Right Even When You’re Not. New York : St. Martin’s Press, 2008. https://www.study.net/r_mat.asp?mat_id=50222973&Crs_ID=30124014&check=passed.

Centola, Damon, and Andrea Baronchelli. 2015. “The Spontaneous Emergence of Conventions: An Experimental Study of Cultural Evolution.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112 (7): 1989–94. doi:10.1073/pnas.1418838112.

Kuhn, Thomas S. 1962. “Chapter XII: The Resolution of Revolutions.” In Structure of Scientific Revolutions (9780226458083), 144. https://www.study.net/r_mat.asp?mat_id=50222972&Crs_ID=30124014&check=passed.